“If you keep your head down, no one will bother you.” Life in Turkmenistan’s prisons

16.05.2019

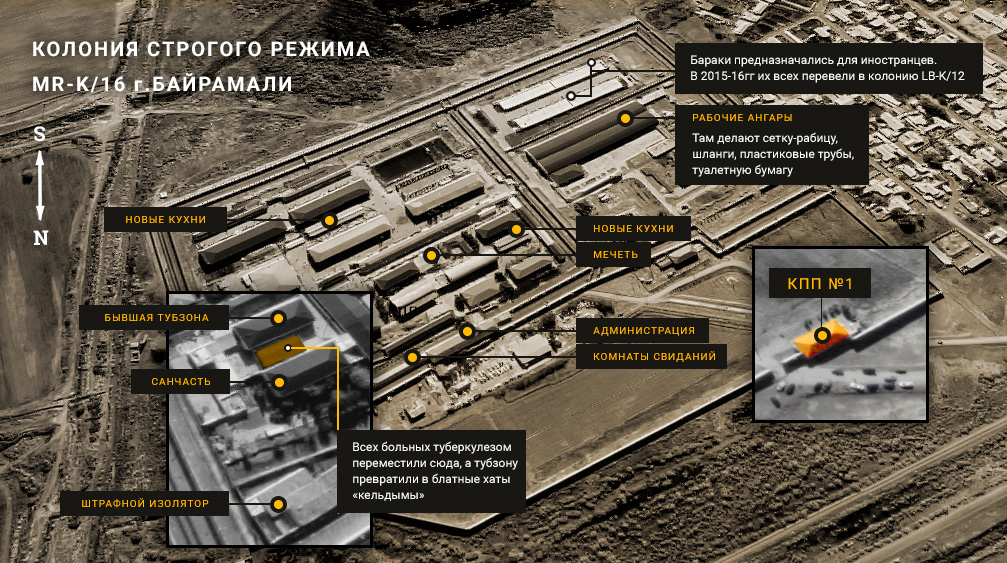

Turkmen.news is continuing its series on the situation in Turkmenistan’s penitentiaries. Corruption is rife throughout the system. In the interview below a former prisoner describes how ex-ministers and other wealthy convicts buy themselves relative comfort at a price in strict regime colony MR-K/16 in Bayramaly. He says that “money can get you anything” in the most corrupt penitentiary in the country.

The first installment in the series looked at life in what is considered a model prison colony, AH-K/6, in Tejen. However, it achieved this status only recently. Before that it was notorious for its extreme punishments. One was to make a prisoner stand for two days in the direct sun without water or food, not allowing him to sit or even faint.

Atanazar, 38, served 15 years in MR-K/16

– Why do you think the Bayramaly colony is the most corrupt in the country?

– Because it’s where the richest prisoners do their time — from former ministers, their deputies and governors to big businessmen. While I was inside, three ministers of water resources and many other equally rich ex-officials served their sentences there. They’re used to comfort and privileges and are ready to pay for them on the inside too. And they pay handsomely: there’s a flood of money from them, their families and other prisoners to the colony’s management, meaning the administration can afford to buy off inspectors or visiting commissions and deal with any issue.

– How does the corruption work?

– Everything there costs money. If you’re the relative of a prisoner, you have to give a bribe at the first entry control point. If you want to drive into the colony’s territory to avoid lugging bags of groceries 200 meters to the main entry control point – pay 50 manats [around $2.5]. Or leave your car outside the gates and carry those bags yourself. Relatives bring a heck of a lot: dozens of kilos of rice, macaroni, sugar, meat, cotton seed oil, vegetables, fruit, some of it by the sack full! What’s 50 manats in comparison?

Next there’s corruption at the entry control point.

Officers of these two services often get on badly and the reason is always money. If the head of the army detail thinks the head of the colony has shortchanged him, he can ban visits, and whatever you do you won’t be able to see your relative that day or give him what you’ve brought with you. But usually the bosses sort these things out between them quickly, because there’s big money at stake.

Greed and profiteering are the order of the day at the screening point for food parcels. Say you’ve brought 50 kg of food and you’re told that only five are allowed. What are you going to do with the other 45? The problem is soon solved for 200-300 manats [around $10-$15], depending on who you are and who you’ve come to see. For “just” 100 manats [around $5] they won’t crumble up your bread, open up your jars and cans or cut your salami into little pieces.

You have to pay for the visits themselves too. In the colony every Internal Affairs Ministry officer has visiting rooms allocated to him and there are 30 of them in all. For example, the head of the penitentiary and his deputies have two or three rooms, the head of the high-security and operational sections one or two. Only these people give permission for the rooms to be used and for money too. They are usually rented out to the ex-officials, to whoever is prepared to pay to jump the waiting list or to spend more than the permitted time with their relatives. Only their unofficial owners can go in and make use of them. The other visiting rooms are shared – that’s so that the other staff don’t go without.

The scams with foodstuffs in the canteen are something else. There are about 5,000 prisoners in the colony, and food is brought in accordingly. However, only around 300 prisoners go to the canteen while the rest do their own cooking. They’ve even built a kitchen for them so that electric hobs don’t pose a fire risk in the barracks. What happens to the other foodstuffs? They’re all sold to the prisoners – bread, vegetables, grains, meat, the whole lot. When they make patties they put in 20 grams of mince instead of the usual 100 and make up the difference with breadcrumbs.

Corruption reaches its peak in deals for the best cells or cushy pads. A simple example: the colony had a good sized barracks for TB patients. Then the inhabitants were rehoused in another building, half the size, and the barracks were turned into cushy cells for ex-ministers. The price of the pad depends on its size. If it used to be an office, then the price varies from $15 to 20,000, but if it was a whole section from which prisoners have been moved out, then the price goes up to $50-70,000.

– In the turkmen.news documentary film “Turkmenistan: Life Behind Bars” a former prisoner says that in 2014 food really improved in the colony. So why do just 300 people use the canteen?

– The food did improve, I guess; for example, they started giving boiled eggs and butter for breakfast. But either they don’t know how to cook dinner or deliberately mess it up: right at the end they might pour a liter and a half of cotton seed oil into a 300-liter vat of soup, so it’s supposedly high calorie.

But that’s not the way to do it. But yes, there has been an improvement, especially in comparison to the days when borsch could be mixed in one vat with yesterday’s pilaf and you found macaroni in the fish soup.

– Can money get you goods that are banned in the colony?

– Money can get you anything: palatial pads, gambling, alcohol, opium – the guards themselves protect the racket. The most brazen who run a wholesale contraband operation are often nabbed by the National Security Ministry.

– Why do they take the risk? They’ve got a good salary with police benefits and privileges, plus income from less criminal activity – the system of visits and parcels.

– First, it’s everyday envy. When cops see other cops driving around in expensive cars, having several apartments and keeping second families, they want the same. Second, it’s greed. However much you earn, it’s never enough. The income from visits and parcels is loose change compared to what they could make on bringing in opium or tramadol. In spring 2016, for example, the National Security Ministry nabbed two guards in the high security section – Guvanch and Samed, two brazen, inhuman thugs. It emerged that Guvanch had brought seven kilos of raw opium and 25,000 tramadol tablets into the colony. They said that the relatives of convicted drug dealers paid him up to $15,000 per kilo of opium! That’s the kind of money we’re talking about. How many other guards are still bringing in drugs today?

– Are there any decent officers? Is there physical violence towards the prisoners in the colony?

– There are – you do meet decent ones, but they don’t stay around for long. They’re destroyed by the system itself. There was a good deputy head of the colony – Tofik Aliyevich [the turkmen.news interviewee cannot remember his surname]. He was a sportsman himself and he got the prisoners into sport too, especially football. He divided people into teams and every holiday held tournaments. To motivate the prisoners he gave the teams generous prizes. The players in the winning team would get a free, extra 24-hour visit and 300-manat vouchers to spend in the colony shop. The runners-up got two-hour visits and 200-manat vouchers. The third placed team got two-hour visits as well and 100-manat vouchers. This was real motivation for the prisoners.

If an interesting game was on TV late at night, Tofik Aliyevich would put a huge TV outside and the prisoners could watch the game, no matter how late it was – 3.00 or 4.00 in the morning.

But there was an incident in the colony in 2015. Two drunk prisoners got into a fight and one slit the other’s throat with a knife. News of the incident reached Ashgabat and they sent an inspection team. They really went for the head of the penitentiary and found out everything that was going on there. Many heads rolled. From what I heard Tofik Aliyevich was even put in prison. The scandal must have been so big that even knowing the minister, Isgender Mulikov, personally – they had worked together in criminal investigation in Ashgabat – couldn’t keep him out of prison. But he wasn’t in for long, just a few months.

– Where did the deputy head of the colony get all that money for the prizes? Is there still that kind of incentive?

– He didn’t give them out of his own pocket. He got the ministers together and lumbered them with it. For a while after he left there were still incentives, but then all the visits were made two hour, and they stopped giving out vouchers altogether. Now there are no visits either.

– You didn’t mention physical violence…

– Now it’s rare for the guards to beat up the prisoners. It may be because of the work of the commission from the department for corrections who eventually respond to complaints. But if one of the staff has it in for a prisoner, they’ll bring in the riot squad who’ll beat the poor guy to a pulp in the punishment cell. You can’t touch the riot squad.

– Ask a prisoner if he’s guilty and he’ll usually say he’s not. Is that really the case?

– Really around five in 100 people are inside for nothing. One person may have been fitted up for a crime – they torture you so much during the investigation that you’ll confess to anything; another may have been treated as an accomplice though he was really a witness to the crime or just a passer-by; or a third may have learnt to pray the namaz from someone who studied in an Arab country and who has been imprisoned for Wahhabism. What are these people guilty of?

The remaining 95 are inside for an offence, but the question is, does their punishment fit their crime? Why do officials who stole tens of millions of dollars from the budget get the same length of sentence as those who took drugs but didn’t deal in them, or stole a purse or snatched a necklace off someone in the street? Why do multiple murderers get out of the colony earlier than those who attempted murder?

These guys are told: the murderers have committed their crime and calmed down, but you’re still angry because you haven’t got what you wanted. You can’t be let out. If we set you free, you’ll go and finish off what you started.

Several gangs were operating in Ashgabat in the early 2000s. Their members would get in a taxi, kill the driver and strip down the car for spare parts. They had some 50 murders to their name. Because of them the authorities insisted on ID cards to travel anywhere: there was a ban on travelling from the city to the countryside without documentation. In the end they got the gangsters and sent them down for 20 to 25 years, but they were pardoned and freed after serving 10 to 11 years. Whoever had been convicted of attempted murder had to carry on serving their sentence.

– How can those five innocent prisoners get justice?

– They can’t. Once you’re in the colony, there’s nothing you can do. No commission will consider your case and there’s no point writing letters to the authorities, not even to the president himself. It will only make things worse.

– Do the guards carry firearms?

– No, weapons are forbidden inside the colony. The prisoners could get hold of them.

– Imagine we are two of those five innocent prisoners. We get together and take two guards hostage, demanding to be heard and to have our case re-examined as we’ve already served five years and have another 10 to go. Wouldn’t such a desperate move prompt a rethink? What would happen in such a case?

– No one would hear or rethink anything. They couldn’t care less about the prisoners and what happens to them. At first they might talk, ask you not to do anything stupid, promise not to report anything if you release the hostages. If this doesn’t help, they will bring in your parents and try to influence you through them. The third option – they will promise to review the criminal case, but the result will be the punishment cells, beating, another trial, an added sentence in a closed regime – you won’t get out of there alive.

There was a similar case in the 1990s in the remand prison in Mary. The prisoners took two officers and demanded their release, threatening to kill both the guards if their demand wasn’t met. That was it: the OMON arrived, lobbed in two grenades and killed them all.

Turkmen.news has not managed to obtain confirmation from other sources that such an incident really did take place in the Mary remand prison.

Interviewed by turkmen.news correspondent Selim Haknepesov. To be continued…

16.05.2019

12.05.2019

25.02.2019

Petrofac Back in Favour in Turkmenistan After Falling Foul of Berdimuhamedov

18.03.2024

Murder and Suicide at Troubled Turkmen School

28.02.2024

Turkmen Prosecutor’s Office Claims Baloch Detainee’s Fatal Wounds Were Self-Inflicted

01.02.2024

Low Prices Lead Turkmen Farmers to Sell Cotton Harvest Residues for Fodder

19.01.2024

Young Man Tortured to Death by Law-Enforcement Officers in Turkmenistan (video)

21.12.2023

Tell us!

Add comment

your e-mail will not be published