Is Turkmenistan Turning Its Back on Lucrative Foreign Tourism?

06.05.2019

It claims to be the Motherland of Prosperity but Turkmenistan’s economy is in chaos and its financial system isn’t working. Many Turkmen begin their day not with a cup of coffee or journey to work, but with a trip to the shops at 6 a.m. to buy a kilo of sugar, as it may disappear from the shelves later, or to stand in line outside the bank.

“Lists”, “standing in line”, “papers”: these words have become firmly established in Turkmen vocabulary. They are essential for ordinary citizens without connections or anyone “having their back” – another expression popular today – if they are to solve any of the myriad problems of daily life. Turkmen.news correspondent Azat Hatamov has decided to focus on just one problem area – the deliberately complicated banking system.

Can turkmen.news readers from, say, the U.S. or U.K. picture the scene: a resident of Syracuse has to go to Washington D.C. or a Glaswegian has to go to London just to unblock their bank cards? Everyone is used to this way of doing things in Turkmenistan – an ordinary resident has to drop everything and go to the capital to solve what seems to be a minor problem.

A line forms from 6 a.m. every day outside the State Bank for Foreign Economic Affairs on Moskovskiy Prospect (now 1945 Street). At 6.30 people start to compile lists for just four counters (numbers 30-33), which deal with bank card problems, as that’s where most of the people want to go. The customers wait for several hours until the bank opens at 9.15, by which time there are already hundreds of names on the list.

Bahar, 40, from Ashgabat has been to the bank before. She runs a business and often has to travel to Turkey. She says she used to have no problem with the card. Like everyone else, she could withdraw up to $50 every day, though sometimes the ATMs in Istanbul would not issue more than $20 in liras. But on her last trip the card was useless – the ATM paid out nothing.

“When I arrived in Ashgabat, I found out that the bank had blocked the card, supposedly for suspicious frequent use abroad,” Bahar says. “In theory it’s not a problem to come and show the departure stamps in my passport to prove that I was actually abroad on the days I withdrew money, but just look at all the people here!”

Bahar usually cannot bear all the waiting and leaves, but today she is determined to sort out her problem, as she will soon be on the road again. In five to six days in Istanbul Bahar withdraws around $170-190. She brings the money back to Turkmenistan and changes it for manats at a market rate. As a result of the difference between the official and market exchange rates Bahar receives five times more than she initially placed on her card in manats.

Practically everyone who visits the bank uses this simple way to make money, but far from everyone manages to show that they were abroad on the days money was withdrawn. Many give their cards and PIN codes to acquaintances who withdraw the dollars and bring them back to Turkmenistan. The bank is tough with them, depriving them for life of the chance to use the international payment cards.

“The bank clerk said I would have to wait up to six months to get a VISA card!” a man called Gayip says indignantly. His son is about to go to university in Bashkiria, but the family is unlikely to be able to get a card before he leaves. They will have to send the card later via other people.

Parents of students studying abroad make up the second largest number of people standing in line. Young people in Belarus, Russia, Ukraine, and other countries have the same problems: an extremely restrictive limit on cash withdrawals and, consequently, a lack of money for the essentials and debts for tuition and accommodation in a dorm or rented apartment.

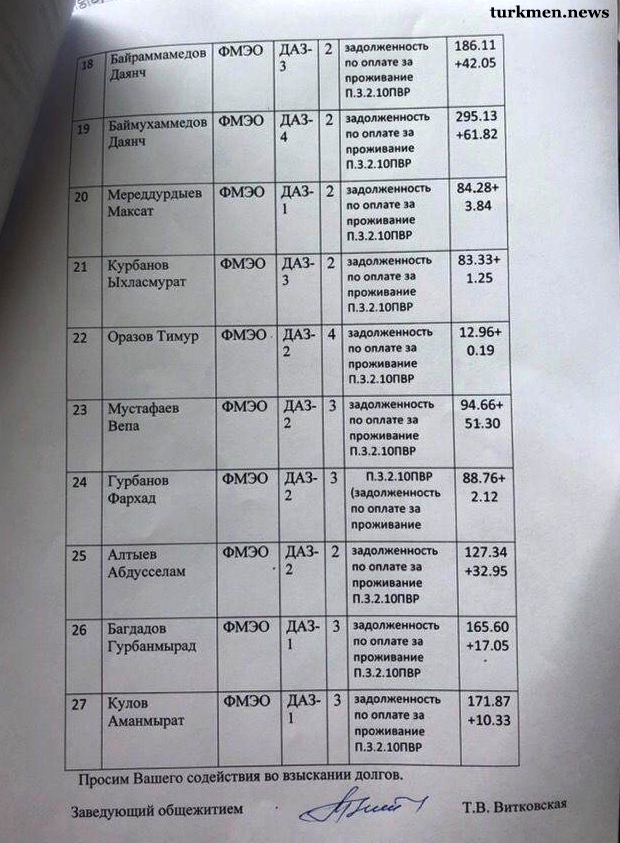

Universities in Belarus, for example, have stopped making allowances for Turkmen students’ economic problems and now set tough conditions – debts have to be settled by a set date, or it’s goodbye. In April three students were expelled from the Belarusian State Economic University alone because of their debts, while two more students were expelled in May. An order expelling another nine students is awaiting the rector’s signature.

“My daughter complains that she can withdraw up to 30 Belarusian rubles [around $15] a day, but on some days she can withdraw 10 rubles and on others nothing at all,” one mother says.

She describes cash withdrawals as a complete shambles. First of all, everyone has a different cash limit for some reason. One student can withdraw $180 a month, while another can withdraw $270. To avoid the card getting blocked, the students compile and carry with them a timetable for cash withdrawals. It shows the whole year, like a calendar; if the student manages to withdraw money today, he or she writes the amount and exact time in the timetable. Money cannot be taken out the next day until after this time. If the limit has been reached, there is a break, then the students check the timetable to see when they can start withdrawing up to their limit again.

“It looks like this can happen only in our country,” the woman tells turkmen.news. “And the situation gets worse every year. There are always some new restrictions and requirements: show us this, show us that, and every time you have to go through all this hassle just to take out your own money!”

Observers say the state should stop artificially maintaining the exchange rate. Despite the fact that at practically every government meeting the president raises the issue of creating a market economy and making the transition to market relations, the state keeps a firm grip on one of the main foundations of the market – the free circulation and exchange of money, and does it unprofessionally, harming itself, private business, and ordinary people in the process.

Whoever has unrestricted and unlimited access to currency conversion can make a fortune thanks to the presence of two exchange rates. The people standing in line know this only too well, but don’t name names.

On the second photo: An incomplete list of Turkmen students who are in debt at a Belarusian university. To work out the debt in dollars, halve the ruble figure.

Azat Hatamov, turkmen.news

Upmarket Bar in Ashgabat Closed After Brawls Involving President’s Cousins

08.04.2024

Turkmenistan’s Defense Minister Deprived Officers From Housing Entitlement Despite Widespread Resignations

28.02.2024

Murder and Suicide at Troubled Turkmen School

28.02.2024

Turkmen Prosecutor’s Office Claims Baloch Detainee’s Fatal Wounds Were Self-Inflicted

01.02.2024

Young Man Tortured to Death by Law-Enforcement Officers in Turkmenistan (video)

21.12.2023

Tell us!

Add comment

your e-mail will not be published