Restrictions Fail to Stop Turkmen Trips to Uzbekistan to Withdraw Cash

20.11.2019

On April 12, President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov gave the chairman of the State Committee for Tourism, Serdar Cholukov, yet another dressing down. A year ago, in January 2018, Cholukov received a presidential reprimand and final warning. Both reprimands were caused by failings and poor performance in his work. In effect, the president is showing his dissatisfaction with the low level of hard currency income from the tourism sector. This income could be a major boost to the country, which is in the grip of an economic crisis.

Less than two weeks later, on April 25, the president demanded that the head of the migration service, Mergen Gurdov, keep rigorous records of all foreigners arriving in the country.

The two contradictory actions reflect the Turkmen authorities’ ambivalence about foreign tourism: a desire for hard currency income countered by fear of foreign influence. Turkmen.news correspondent Azat Hatamov looks more closely at the current state of tourism in Turkmenistan and considers its potential.

Almost 10,000 Turkmen citizens visited Georgia in 2017, a higher percentage than from any other CIS state, according to figures from the Georgian National Tourism Administration. In the whole of 2016, just 6,000 foreigners visited Turkmenistan, including those who came to the country as part of official delegations.

In 2018, 8.7 million tourists visited Georgia, which has a population of 3.7 million. According to data from Georgia’s National Bank, income from foreigners in 2018 exceeded 3.2 billion dollars and made up 7.6% of GDP. Over the past 10 years Georgia has increased its profit from foreign visitors more than sevenfold, while Georgia’s near neighbors take the top four places in terms of visitor numbers: Russia (over 22%), Azerbaijan (over 6%) and Turkey and Iran (over 5% respectively).

Impressive figures? Well, here’s some more food for thought: 7.6% of GDP is approximately the same amount that Turkmenistan earns from the production and sale of cotton.

Yes, Georgia has fabulous cuisine and excellent wine, interesting historical sites, mountains and the sea. But Turkmenistan has all this too, plus the mysterious Karakum desert with its unique gas crater and canyons, underground lake with warm water all year round and dinosaur plateau, and, last but not least, the Great Silk Road passed through Turkmenistan.

Last year, 2018, was even officially named “Turkmenistan—Heart of the Great Silk Road”. As for history and ancient oriental architecture, we have Merv and Koneurgench. Every region of Turkmenistan has a rich array of tourist attractions. Every region could welcome thousands of tourists every year, providing work for local people and filling the public purse with tax revenue.

On one of the warm spring holidays, I went with my family to Bagir, a village 20 km from Ashgabat. This is the site of the ancient city of Nisa, founded in the 3rd century BCE and a true treasure of world history.

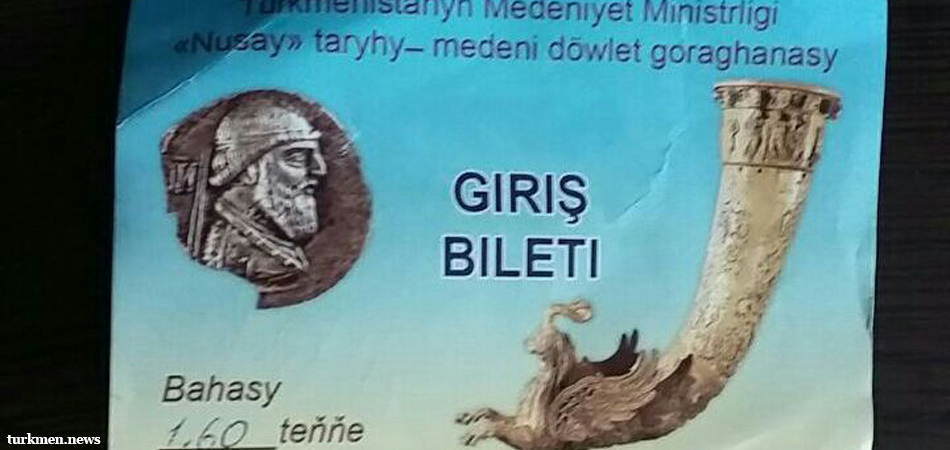

At eight in the morning the ticket office was still closed. The few passers-by said we could just go in, but we decided to wait for the cashier and pay the entry fee. He arrived half an hour later, still half asleep, and amazed that anyone should have come on a holiday, instead of going to the market or to see their relatives in the village.

Old Nisa is interesting if you know the history of your area, but foreigners won’t be able to appreciate it without some information. There isn’t a guide who could explain everything, or boards with illustrations or information such as “this is where the Parthian kings were buried”. Mind you, there’s no one to read them: we were the only visitors to the ancient city all day, contributing 6.4 manats to state coffers (30 American cents at the market rate) for entry tickets, or 1.6 manats per person.

The huge car park is empty. There’s no café nearby, nor toilets, but there is a hall for functions and a restaurant, closed when we were there, though they’re both a bit of a hike on foot from old Nisa. Foreign visitors would create potential for souvenir shops and fast food stands, providing work and income for local people.

Another day we visited a place that changed the fate of modern-day Turkmens and the country as a whole—Geok-Tepe fortress, scene of the Turkmen defeat to the Russian army in 1881. And there was no one there!

At the railway station dozens of local taxi drivers whiled away the time, discussing the latest ban on dark-colored vehicles. A huge museum and Saparmurat Haji mosque (named in honor of the country’s first president, Saparmurat Niyazov) have been built at the historical site. In 2008, $34 million from the budget were spent on reconstruction of the mosque. For whom, one might ask. A middle-aged Turkmen man arrived at around midday, sat at the wall, prayed and left. I hope that his appeal to the Almighty included a request to send wisdom to those in Turkmenistan who take decisions on the country’s economic, social and cultural development.

Of course, we won’t catch up with Georgia straightaway, even if the authorities of Turkmenistan suddenly wake up and copy their model of tourism development. Citizens of nearly 100 states can enter Georgia without a visa for a period from one month to a year. The visa-free regime applies to our compatriots too, who are making good use of it, judging from the tourism administration’s statistics. In Georgia there is no migration service—one of the main obstacles to tourism development in Turkmenistan, as the crossing of the border is a matter for the police. It takes just a couple of seconds to get through passport control and that’s it—Welcome to Georgia! Georgia has abolished the pointless system of compulsory registration at one’s place of residence too, though in many CIS countries this legacy of the Soviet era is still in force.

In 2018 former Turkmen citizen Atabay travelled to Dashoguz from Russia’s Tyumen region and spent one night staying with different relatives from those he had mentioned in his visa application. That evening employees of the migration service came for him and told him to return to his place of registration. Atabay had to pay a hefty fine too and was threatened with deportation for breaking the rules for visiting the country. It was only because his relatives knew someone that they managed to smooth things over. And this is a former compatriot! What’s the point of all this bureaucracy, of paying wages to dozens of people and special departments, and spending a lot of money on them?

Taking as a basis the Georgian statistics for population and the number of foreign visitors, then some 12 million tourists could visit Turkmenistan in a year. Of course, this is beyond our wildest dreams at the moment, but just imagine one million foreigners visiting our country. Visas should either be abolished completely or stamped in the passport on arrival in the country for, say, $20. The country could earn $20 million dollars in hard cash on visas alone. That’s 400 million manats or a year’s salary for 22,222 Turkmen (at 1,500 manats a month).

If every tourist spent $250 during their stay in Turkmenistan (on transport, accommodation, food, local transport, tour guides and souvenirs), and that’s according to the most modest figures, income from them would be $250 million or 5 billion manats, which is a year’s salary for over 270,000 people.

With an increase in demand for flights to Turkmenistan and favorable prices for jet fuel European aviation giants such as British Airways, Air France and KLM could regularly fly to our country, while Lufthansa could introduce a flight to Ashgabat from Munich too. Turkmenistan Airlines would finally be able to introduce profitable routes to Europe and southeast Asia. This would mean additional jobs at the capital’s now deserted, $2.3 bn airport. Ah, we can but dream…

Our country has all the prerequisites for the development of tourism: sights, scenery, and a reasonably developed tourist infrastructure—a large number of new hotels, restaurants, entertainment facilities, tourist firms with their own guides, interpreters and vehicles.

The state could stop running all the hotels and sell them in an open tender or give them to world famous chains to run, such as Four Seasons, Hyatt, Holiday Inn and Best Western. The new owners would mean new investment in Turkmenistan’s economy and international standards of service. The country already has experience of working with western chains. In the 1990s the Sheraton Grand Turkmen Hotel appeared in the center of Ashgabat and in the Berdimuhamedov era— the Sofitel Oguzkent. However, a few years later both hotels removed the signs of the famous brands and started to call themselves simply the Grand Turkmen and Oguzkent.

But the most important thing is that the people of Turkmenistan are hospitable, ready to learn and to develop exclusive services for foreign visitors. Just one thing is missing—political will on the part of the country’s top leadership, nurtured on the fear from deep within the National Security Ministry that every tourist could really be a cunning spy.

However, even if Turkmenistan follows its neighbors’ good example, this doesn’t mean that crowds of tourists will immediately flock to our country. We still have to fight for them—to offer something unique, to simplify access to the country and not to keep tabs on every flash of a camera.

P.S. It was while I was preparing this analysis that the news came in of the president telling the head of the migration service, Mergen Gurdov, to keep strict records of foreigners arriving in the country.

What more can I say? It is probably no coincidence that the two tourism success stories in this report—Georgia and Kyrgyzstan—have far more democratic governance than Turkmenistan.

Azat Hatamov, reporting from Ashgabat

Upmarket Bar in Ashgabat Closed After Brawls Involving President’s Cousins

08.04.2024

Petrofac Back in Favour in Turkmenistan After Falling Foul of Berdimuhamedov

18.03.2024

Turkmenistan’s Defense Minister Deprived Officers From Housing Entitlement Despite Widespread Resignations

28.02.2024

Murder and Suicide at Troubled Turkmen School

28.02.2024

Turkmen Prosecutor’s Office Claims Baloch Detainee’s Fatal Wounds Were Self-Inflicted

01.02.2024

Tell us!

Add comment

your e-mail will not be published