Pneumonia Ravages Turkmenistan

29.07.2020

The information in this report has been provided by turkmen.news monitors in Dashoguz, Lebap, and Mary regions. In order to protect our sources we do not name the precise locations where monitoring is conducted or publish photographs of fields, identifiable locations, or assembly points in which people’s faces can be seen.

This is the situation in the districts of Koneurgench, Gubadag, and Boldumsaz in Dashoguz region, and in the districts of Garagum, Mary, and Oguzhan in Mary region. Spring rains and floods followed by the summer drought mean that dozens of the larger tenant farmers have no harvest. Farmers in Dashoguz region say that not only did the irrigation channels that usually supply water for the fields dry up this summer, the drainage ditches did too, though their water is not fit for irrigation.

“We’d even have been glad to water the fields with the dirty drainage water, if there’d been any, but the pumps were idle this summer on all the farms. As a result, the cotton stalks scarcely reach the height of a youngster’s knee, while the bolls are the size of a walnut,” a tenant farmer in Koneurgench said.

This season public sector workers were sent to pick cotton before the official start of the harvest campaign, which in the northern region was September 16. At the end of August there was nothing ready to harvest, as many tenant farmers had to re-sow their cotton after the heavy rains in mid-May. There will be no harvest at all on some farms – the heads of several farmers’ associations in Boldumsaz and Koneurgench districts refused to help the affected farmers with equipment or seeds for re-sowing, so the farmers decided not to bother as they could not afford the expense. As a result, half of the area allocated to cotton in Dashoguz region had not been sown at the end of May.

Where tenant farmers did use their own resources to grow at least something, the cotton looks straggly and uncared for, and the fields have many bare patches without a single stalk.

Many villagers do not support the arrival of “help from the city” because of the small amount of cotton. Nevertheless, some do agree to accept help and even pay the pickers 0.30 manats (13 U.S. cents) per kilo of cotton.

“On Sunday September 27 I picked just 4 kg of cotton, but didn’t really make an effort, as nobody had given us any targets,” a young man told a turkmen.news monitor in Dashoguz. He had gone to harvest cotton in place of his parent who works in the public sector. “Cotton picking is seasonal work for some of our group, who seek to earn as much as possible, but even they could not pick more than 16-18 kg each the entire day.”

Nevertheless, officials are making the farmers’ associations accept help from the cities in order to show their superiors that they are actively involved in the harvest campaign. Both the forced laborers and the tenant farmers have the impression that no official is actually organizing the process. The public sector workers who come to “help” often have to find somewhere to do their compulsory service themselves, while the farmers’ associations are surprised when pickers suddenly turn up.

“We arrived but were not sent to any farm, so we had to look for a field ourselves,” an employee of a state institution in Boldumsaz district, Dashoguz region, said. “We finally found somewhere. The tenant farmer wasn’t pleased to see us, but agreed to let us pick cotton. He said he was ready to pay 0.30 manats per kilo, but that he had no small change. There was very little cotton – on average one worker couldn’t pick even five kilos a day. In the end the group had to club together and pool all the harvested cotton so that the farmer could pay us in large-denomination notes, and then we had to divide them up ourselves. My income from a whole day of work was 1.5 manats. For comparison, a bottle of vegetable oil at our district market costs 23 manats ($1). Many pickers think that the tenant farmers pay them too little, just 0.30 manats when the state buys the cotton for 1.40 manats. I understand that when the farmers’ associations hand in the raw cotton, some of it is written off because it has impurities or is damp, and of course they have to cover all the costs of sowing and tending the soil, and they have to make some sort of profit at the end of it all. So if you tell them you’re not happy, the farmer replies reasonably: I don’t even have to give you this. I didn’t ask you to come.”

The small quantity of ripe cotton may also be a reason for the lack of rules or a system for sending public sector workers to the fields. Teachers in Turkmenabat are obliged to contribute money twice a week to hire workers, and to go to the fields themselves on Sundays or send someone else in their stead. But the situation is different in one district in Dashoguz region: teachers are sent only on Sundays, and not always then – sometimes they’re able to spend their legal day of rest with their families. They are not yet required to pay to send hired workers during the week.

Public sector workers usually have to meet early in the morning, at 6.30, to go and pick cotton. But this doesn’t mean that the convoy of buses will set off soon afterwards. This is what an employee of a state organization told a turkmen.news monitor in Dashoguz:

“Around 150 of us from different organizations went to the district executive authorities at 6.30 in the morning, as instructed. But the transport didn’t turn up until 8.45. It was very cold, around 5 degrees, and windy. People were wearing hoods over their hats and wrapped up in scarves. It was unbearable waiting two and a half hours in the cold wind; some people went home, saying, we came when they insisted we go cotton picking, but nothing has been organized. Then instead of buses for the freezing people they sent a single ZIL pick-up truck, which took the women who had their children with them and teenagers. At the last minute the employers sent their own minibuses for the forced cotton pickers. There wasn’t room for everyone so those left behind had to hitch their own rides. Around 40 people walked five kilometers along the highway, then turned off into the collective farms and walked another three kilometers to get to their destination. This group included youngsters who were going picking in place of their parents or to earn some money. People walked on the side of the main highway from Dashoguz to the districts and there was a real danger they’d be run over by a passing vehicle. It’s not safe on the collective farms either. There aren’t many people or cars about, but there are lots of dogs. The men in our group only just managed to beat off a furious sheepdog that had taken hold of a young woman’s leg.”

Residents of Mary’s first residential district usually assemble at 6.30 near school No. 14 on Bauman Street to go to the cotton fields. Buses set off as soon as people have taken their places, but the drivers stop en route to pick up groups of people who have been given different pick-up points in the city – near Merv Bazaar, the book shop or school No. 1. They are mainly people from the third residential district and the city center.

No one is concerned about the safety of the pickers from the city. No one cares if transport safety measures are observed or if the buses, minibuses, and trucks are properly maintained. The driver of the ZIL pick-up knows perfectly well that he could be fined for carrying people in the back of his truck, but he also knows that no one has time for the finer points during the cotton harvest campaign – following the orders of the bosses is all important. The traffic police don’t accompany the pickers’ transport.

The same goes for officials – they won’t be held responsible if something serious happens or one of the public sector workers walking to the fields is run over. The local authorities are responsible for finding and sending people from the towns to the farmers’ associations, getting them there, and allocating them to individual farms. This work has been badly organized in all three regions to judge from the monitors’ reports.

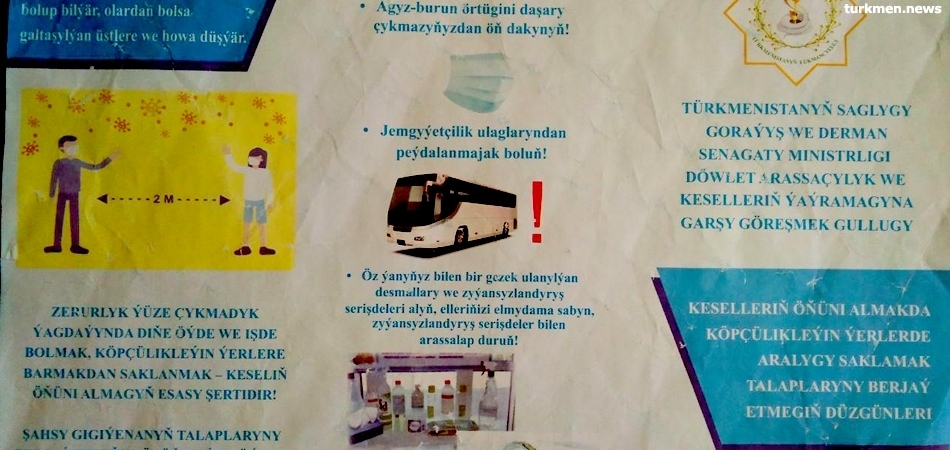

Epidemiological safety is a special subject during the coronavirus pandemic. The authorities of Turkmenistan still do not acknowledge the presence of COVID-19 in the country, but have introduced tough public health measures in the cities. There are reports from Turkmenabat and Mary, for example, of buses of police cruising through the cities. They pick up anyone out and about without a mask and take them to the police station, where they are fined 22 manats (around $1) for breaking the mask rules and let go. In Mary bus passengers are checked mainly at the city’s Green Bazaar stop. The police take a look on board the buses and remove anyone who is not wearing a mask. Turkmen.news reported previously that drivers of suburban buses are fined if they take more passengers than there are seats.

However, it looks as though these measures do not apply to the “crack cotton troops”. According to monitors, around half of the public sector workers sent to the fields have a cough. No one is bothered whether this is coronavirus or a seasonal cold and there’s no mention of masks or other precautions.

People are taken to the cotton fields in overcrowded buses. Teachers in Mary are amazed: there are posters in school about the importance of keeping a distance and not using public transport because of the danger of COVID-19 infection, but no thought is given to social distancing when people are sent to the fields. The way people are taken in overcrowded buses to the cotton fields provides further proof that these rules do not exist for officials who are concerned only with the “harvest battle.”

Monitors report there are quite a few youngsters in the fields this season. They look to be children between 10 and 16 years of age. Some go cotton picking in place of their parents who are public sector workers, while others are hired for money in place of adults.

A pupil in the ninth grade at secondary school in Dashoguz region told a turkmen.news monitor why he picked cotton on Sundays.

“Mum works in the culture department and always goes herself, but she’s not well, she’s got a high temperature. Her boss told her by phone that she should send a hired worker instead. But we would have to pay him and we’re in debt. We decided at home that I would go instead of mum, since there’s no school on Sundays anyway. Last Sunday I picked 12 kg. Six out of 32 people in our class pick cotton: four boys and two girls. Two go as hired workers to help their families, while the others go instead of their parents. It’s about the same in the other classes. The class leaders and school principal understand the situation. It’s even in their interests, as they can reduce the number of pupils and divide the classes into 15 pupils each to meet the new public health requirements. Otherwise, if there is an inspection and there are too many pupils in class, they’ll have problems. But there are far fewer inspections this year. Teachers say among themselves that the staff of the district education department try to keep school visits to a minimum out of concern for their own health, so they sort out all the issues with the school principals by phone.”

The practice of sending large numbers of schoolchildren to the cotton harvest stopped during the rule of Turkmenistan’s first president, Saparmurat Niyazov, while his successor, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, has made tough statements about child labor. Since then, adult public sector workers, including teachers, have been forced to go to the cotton fields. However, the ban on using child labor is being broken more frequently.

A turkmen.news source said that teachers often send pupils from the senior grades to pick cotton in their place. The teachers ask in class if anyone would like to go cotton picking, and pay the children 20 to 25 manats a day (just under $1.5 according to the market rate). The pupils are marked as present in the class registers, but they are actually a long way away. This isn’t the first year it’s happened. The teachers don’t want to do the backbreaking work themselves, while some pupils are glad to skip class and earn some money at the same time.

Unemployed adults who take the places of public sector workers are paid more or less the same – between 20 and 30 manats. The teachers prefer to pay the pupils, as it’s difficult to find adults willing to work for that sum.

There’s another problem with the hiring of substitute workers. In the 2000s, public sector workers used to have a choice: go cotton picking themselves or pay to hire someone in their place. Then in the 2010s they were banned from going during working hours, so they were left with the choice of either hiring people or paying money to their employers. In many schools in Lebap region principals have now set a new condition: staff give the principal money and he will find people himself, supposedly in the rural areas. Teachers suspect that their managers are using this to make money themselves, as the sums involved can be substantial.

“Until now, a teacher I know always sent her relative cotton picking in her place,” a source in Turkmenabat said. “This person is disciplined, doesn’t drink, picked a lot, and there were never any complaints about him from the teacher herself or the school administration. But this year the principal said that whoever wanted to hire workers to go in their place should not do it themselves, but should give him 20 manats a trip. But nobody knows how many teachers and support staff will have to go cotton picking. Maybe only 20 workers, or just five, will be hired with the money from 30 teachers. Where will the rest of the money go? Will the principal put it in his own pocket? Some teachers dutifully pay up, as long as they’re not hassled about it every time. They say, what difference does it make who picks the cotton?”

The teaching staff at the large schools in Turkmenabat are divided into groups of 30 to 35 people, although the deputy governor for education, culture, health, and sport, Gulnara Jumaeva, insisted at a nighttime meeting on August 28 that the number in each group must be increased to 45. Twice a week one such group must go to the cotton fields. “Go” should not be taken literally, as nobody would allow so many teachers to abandon their classrooms at the same time; it’s all a question of money, as they have to pay up twice a week to hire workers.

This is how the financial scheme works. For example, every day a group of 30 teachers gives the principal 20 manats each, making 600 in total. There are six working days in the week, and every day 600 manats are placed on the principal’s desk – 3,600. Considering that the harvest began at the end of August (in Mary, for example, they started collecting 300 manats from utilities workers on August 20) and continues at least until the end of November, that makes a sum of 46,800 manats (more than $2,000) over three months, excluding Sundays. And this is the cotton collection in just one school! In fact, the cotton harvest can continue until mid-December, and at the height of the harvest in October teachers make three “trips” a week to the fields, rather than two, so that makes an even greater sum.

Petrofac Back in Favour in Turkmenistan After Falling Foul of Berdimuhamedov

18.03.2024

Murder and Suicide at Troubled Turkmen School

28.02.2024

Turkmen Prosecutor’s Office Claims Baloch Detainee’s Fatal Wounds Were Self-Inflicted

01.02.2024

Low Prices Lead Turkmen Farmers to Sell Cotton Harvest Residues for Fodder

19.01.2024

Young Man Tortured to Death by Law-Enforcement Officers in Turkmenistan (video)

21.12.2023

Tell us!

Add comment

your e-mail will not be published